By John Beydler

Copyright 2020, All rights reserved

FOREWORD

Everyone living around Jerico Springs, Mo., in the half-century beginning in 1920 heard of Bill Farmer sooner or later.

My first memory of him is from the summer of 1955 or ’56, when I would have been nine or 10 years old. He was sitting in his car, parked near the far end of the quarter-mile long dirt lane that led from our house to the gravel road connecting us to Jerico and the wider world.

An unfamiliar car parked there, out of sight in a wooded portion of the lane, was quite odd and I was a bit uneasy when I spotted it while en route to the mailbox. As I walked past, the man in it turned his head slightly to watch me go by but otherwise ignored me, as he did when I made the return trip, mail in hand.

I told Mom about the man and the car. She said, “Oh, that’s Bill Farmer. Don’t worry about him.” So I didn’t, even when he was there again the next day, when we again ignored each other when I went for the mail.

After that, I would recognize him and his car when my family encountered him along the narrow dirt and gravel roads around Jerico. He most alway hogged the middle, forcing whoever met him to get over. We would sometimes see his car at the house just down the road from our lane, the home of the widow Hetha Davis. That always provoked my teenage sisters into snickers and speculations about evil motives.

He came to our house two or three times in the late ‘50s. He and Dad would sit in his car for an hour or so, talking politics I assumed, since I’d heard enough adult talk to know Bill Farmer had something to do with politics, in which Dad had some interest.

His name came up in neighborhood conversations now and then and I sensed as time went by that some people seemed uneasy talking about Bill Farmer, even fearful of him. I heard him called “Burnin’ Bill.”

But he was never any presence in my life, and I last saw him circa 1960, the year I started high school.

Fifty-seven years passed before the name re-entered my head. I retired in 2017 after 52 years as a newspaper reporter and editor and have since amused myself in part by researching the history of Jerico Springs. I discovered you can’t do that very long without encountering Bill Farmer.

The old newspapers describe a man once possessing power and influence that reached far beyond Jerico and Cedar County. Often in trouble with the law, always slipping away, the man was more complex and ambitious than many of his contemporaries, perhaps more insightful in some ways as well.

He led a dozen lives, from popular young businessman through disgraced politician to promise-keeping grandfather. His fall was front page news all over Missouri.

For all the several hundred newspaper stories about him I’ve now read, despite the official documents examined and the interviews with some of his relatives and Jerico old-timers, several mysteries remain – including, by the way, what the hell ever he was doing parked in our lane those two summer days back in the ‘50s.

MEET BILL FARMER

Bill Farmer was a small man.

“Short” and “slender” are in the height and weight lines on his World War I Selective Service card. The World War II card is more precise: 5’ 2” and 130.

Dapper and outgoing, Mr. Farmer cast an outsize shadow as the most famous – and infamous – character to parade through Jerico Springs’ history.

Born Sept. 25, 1892, on a farm near Cedarville, about 6 miles southeast of Jerico, John William Farmer’s 93 years included turns as a farmer, car dealer, bank director, cattle buyer, druggist, road construction foreman and pool hall/tavern operator.

Through it all, he was a real estate wheeler-dealer who bought and sold dozens of properties in Cedar and surrounding counties, and a politician who gained a degree of influence in Missouri Democratic circles highly unusual for a man from small and heavily Republican Cedar County.

He was disdainful of the law. “Ralph, you’ll never amount to a damn because you’re too honest,” he often told brother-in-law Ralph Evans, according to Mr. Evans’ granddaughter, Linda Martin.

Mr. Farmer’s life reflected that attitude. From 1929 through 1956 he was charged with at least 20 criminal offenses. Most alleged election-law violations but other charges ranged up to first-degree murder. He was never convicted of anything. A combination of denial, silence, obfuscation and high-powered lawyers – not to mention armed theft of evidence — won him acquittal in every case.

He was never charged with alcohol offenses, though it seems likely he was at least on the fringes of the Prohibition-era booze business.

Neither was he ever charged with arson though Cedar County folklore holds him to be a man who burned his own property for insurance money and that of others for political or personal revenge. Nearly all the half-dozen-plus people interviewed about him in 2019 and 2020 volunteered stories about specific properties he bought that soon burned.

Mr. Farmer’s increasingly sordid reputation was acquired even as he was repeatedly re-elected Democratic committeeman for Benton Township, the job that was the foundation for his political influence. Benton, one of 14 townships in Cedar County, covers Jerico and the county’s southwest corner. It is overwhelmingly rural; farming dominates the economy.

Mr. Farmer won the committeeman job in 1936 and held it, with one short break, until 1958. The numbers vary from election to election but as many as 400 Democrats voted in some Benton committeeman races during that period. All those wins mean he had a solid base of supporters for many years.

Mrs. Martin, the great-niece who as a preteen lived three years with Mr. Farmer, touched on one of the probable reasons for his ability to win friends even as he made enemies: “If he liked you,” she said, “he would do anything for you. If he didn’t like you, then God help you.”

EARLY YEARS

Mr. Farmer was reared on farms near Cedarville. His mother, Nora Lula Farmer (nee Rector), died in 1897 at age 26, when he was four years old. The 1900 Census lists him, his father, Albert, and two siblings as members of his grandfather’s household in Cedar Township in Dade County.

By the time the 1910 Census was taken, his father had re-married and “Willie” was listed as “farm laborer” on the home farm. Later that year, he married Mabel Fern Smith, a neighborhood girl. He was 17 and she was 16. It’s unlikely he had any formal education beyond that offered at Central School of Cedar Township, the one-room school near his home.

The young couple took up farming, raising livestock and row crops on a farm south of Cedarville, near his father and several other relatives. Daughter Catherine Fontella joined the family in 1912; son Wayne in 1916.

Mr. Farmer helped in such neighborhood tasks as keeping the mostly dirt roads in passable shape, getting paid $3 by the road district occasionally. He was probably already buying and selling livestock, a life-long source of income for him

But young Mr. Farmer – “Will’’ to the family, “Little Bill’’ or “Cotton Bill” outside it – had something more than a farm life in mind.

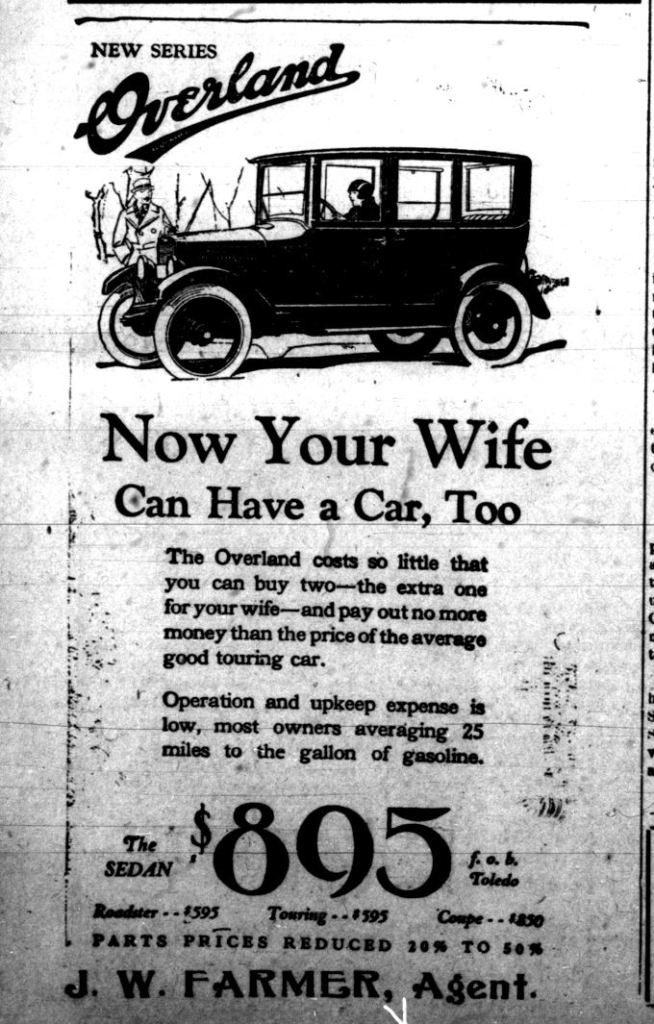

He saw opportunity in Jerico Springs, a seemingly vibrant village about six miles north of his farm; and in the rapidly expanding automobile sales and service business, specifically in the Overland Automobile Co., from which he obtained its Jerico agency.

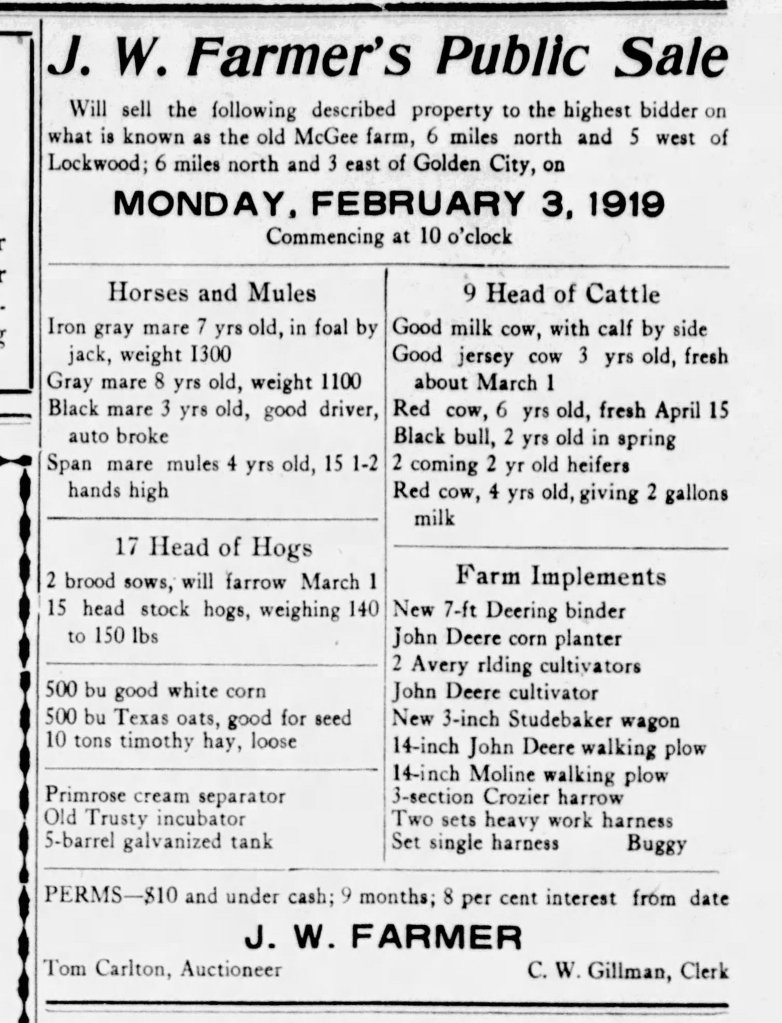

In early 1919, he sold out the farm. The sale bill listed five horses and mules, one in foal; nine head of cattle, 17 head of hogs, 10 tons of loose timothy hay, hundreds of bushels of corn and oats, along with the necessary farm implements. The latter included top brands: a John Deere plow, planter and cultivator; a Studebaker wagon, Moline walking plow and a new Deering binder among them. The land was not included in the sale.

Between the sale proceeds and whatever other resources he had accumulated over his eight or so years on the farm, Mr. Farmer had money to invest when he moved to Jerico.

THE YOUNG BUSINESSMAN

Bill and Mabel Farmer arrived in a Jerico still riding the economic high driven by soaring farm commodity prices during just-ended World War I.

A second bank, The Peoples Bank, opened in July 1919 and took in $43,000 in deposits the first day. By the end of August, it and the existing Farmers Bank had a combined $276,000, equal to $4.1 million in 2020 dollars. The Optic editor bragged that Jerico, with two sound banks, was ready to take on a civic to-do list including “a rock road to a railroad point,” a mill, an elevator and a lumber yard.

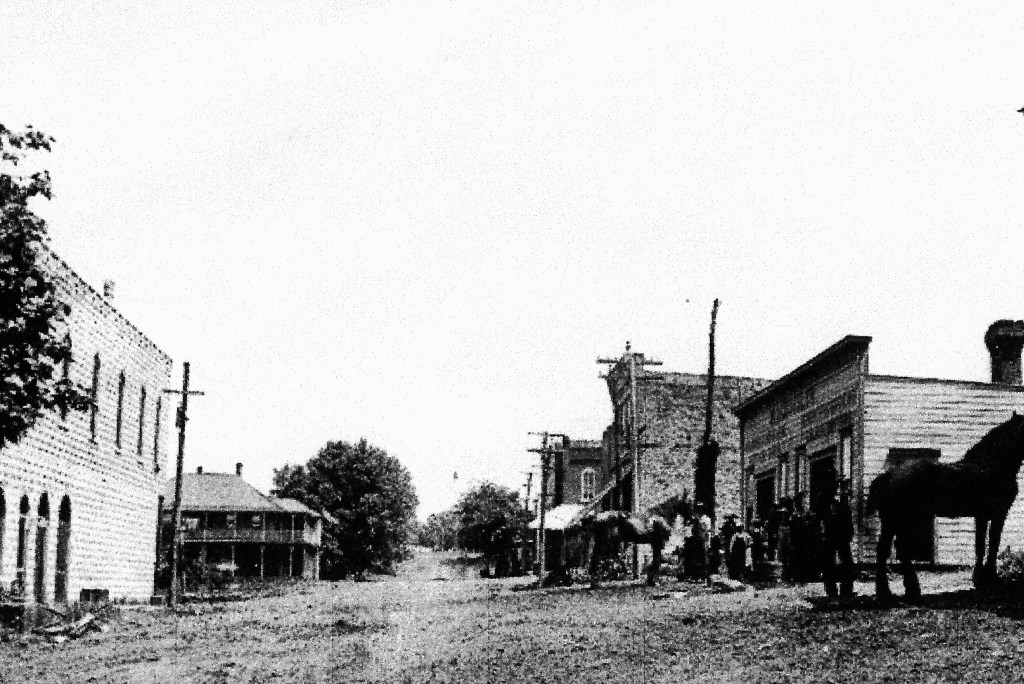

Mr. Farmer contributed more than optimistic rhetoric to the boom. In June 1919, after a brief period of leasing business space, he purchased the Main Street Garage, which would have been on the east side of Main, about a half block south of Broadway. He did business there even as he built a new rock building around the existing wooden one, the Optic reported.

Completed in April 1920, the new garage included a new car showroom as well as a large parts department and the “services of a first-class mechanic who has had 8 months schooling,” Mr. Farmer announced in the Optic. He later told a Springfield News Leader reporter he spent $10,000 building the garage ($140,000 in 2020 dollars).

His early customers included my grandfather, John W. Beydler, described by the Optic as “a prosperous farmer three miles west of town.” He bought a new Overland in September, 1919.

From early 1919 onward, Mr. Farmer, navigating in the highly competitive “garage” business in Jerico, was frequently in the pages of the Optic, as both advertiser and news subject.

Besides Mr. Farmer’s Overlands, a shopper in Jerico could inspect new Fords and Maxwells. Several other brands had sales representatives, if not showrooms. One or two other garages offered used cars and repair services.

He listed himself as a “mechanist” in the 1920 Census, which also reported he and Mabel owned their Jerico home free of any mortgage.

The two forged close ties to Jerico in ways big and small.

The town still lacked electricity and Mr. Farmer sometimes shared power from the generator at his garage, as during the Annual Founder’s Day Picnic in June, when thousands of people flocked into Jerico for food, music, parades, baseball games and speeches. Jerico’s year-end financial report for 1921 noted three payments to Mr. Farmer, ranging from $2.75 to $8.25, for “lighting the park.”

In 1922, he was named a director of the Peoples Bank, which would have required him to be a stockholder and likely a major depositor as well.

Starting in the early ‘20s, he was buying and selling lots and houses in Jerico and farm properties in the surrounding countryside. He also indulged his decades-long interest in buying and selling livestock. In January, 1923, the Optic reported he had bought 37 head of cattle from “the Manley brother who lives … northeast of Jerico” and sold them to “Ralph Evans and Cecil and Doc Pyle.”

He and Mabel were both elected officers of an auxiliary of the International Order of Odd Fellows, Jerico’s most popular civic organization. He was a Mason as well.

Car sales boomed. The Optic often ran lists of people buying cars. Five sales a week were common. One week he sold 10. He “sold cars all over the county,” according to a later story in the Optic. Jerico businessmen traveling to Springfield and Kansas City often drove new cars back to Jerico for Mr. Farmer.

Forty-seven people were waiting at his house when he came home for lunch Sept. 25, 1922, his 30th birthday. The afternoon was “well spent with music and singing,” reported the Optic in an article signed by “One present.” The guests “all departed at a late hour,” the report concluded.

The successful and popular young businessman portrayed in the Optic would have been a striking figure at the time, given his diminutive size and a lifelong tendency to dress well. Talkative and out-going, he was a master salesman who could sell you anything, according to cousin Charley Farmer, who knew him later.

Though he hadn’t yet sought any formal political position, there’s no doubt young Mr. Farmer – already known as a die-hard Democrat — spent much time talking politics with his expanding circle of acquaintances, keeping up with local and national issues as Jerico and farm country in general slid into hard times in the early ‘20s.

FIRES AND BANK FAILURES

The general national prosperity that fed Jerico’s 1919-21 boomlet papered over some grim facts: The town’s population fell by 33.7 percent during the ‘teens, from 395 to 262. Cedar County’s fell by 13. 4 percent, to 13,933.

Farm commodity prices were beginning a disastrous decline as the ‘20s got under way. The Missouri Department of Agriculture said farm products in August 1921 were selling for 51 per cent less than a year previously. They continued to fall, followed by land prices and a migration from farms.

One impact was the rapid consolidation of Jerico’s auto businesses. In June of 1922, Mr. Farmer acquired the Ford agency and became Jerico’s last new car dealer.

A more ominous impact: The Farmers Bank of Jerico failed Dec. 26, 1923, with the failure attributed to loans made in good times that farmers could no longer re-pay. Though a new bank, the State Bank of Jerico, salvaged what sound assets Farmers Bank possessed, it was a smaller and weaker institution.

A few months later, the two remaining commercial garages burned to the ground, Mr. Farmer’s in circumstances that no doubt fanned stories the blaze had been deliberately set.

The Zollman garage, across the street south of Spring Park, burned in April with the loss of a dozen vehicles stored there. Operator William Zollman told the Optic the fire may have started in electrical wires leading from the garage’s generator.

There were two fires at Mr. Farmer’s Main Street garage.

The first, around 6 a.m. June 16, 1924, was noticed by a passer-by who sounded the alarm early enough to save the building and its contents from major damage. The Optic said the blaze began between the ceiling of the office and the roof. “Mr. Farmer does not know just how the fire started, catching where it did in the roof,” the Optic reported.

Some 36 hours later, around midnight June 17, a passer-by again sounded the alarm but help arrived too late to do much more than save neighboring structures as towering flames fed by exploding gas tanks on stored cars consumed the garage. Seventeen vehicles were destroyed, including six new Fords and seven used cars belonging to Mr. Farmer.

The Optic story did not say how or where the second fire began.

The Springfield News Leader said insurance on the building, cars, parts and tools totaled $18,000 ($267,000 in 2020 dollars). Mr. Farmer told the paper his losses would amount to $3,000 more than the insurance.

Mr. Farmer eventually built a new garage, but the second half of the ‘20s was tough on him and on Jerico.

Fire struck again March 1, 1927, taking two large business buildings on Main Street just north of Broadway. One housed C. L. Long’s General Merchandise Store, the other the State Bank of Jerico, a barber shop and the Masonic Hall. The Optic did not report a cause.

The bank building was insured but directors chose not to rebuild. Announcing in the Optic that they felt the town would be better with one strong bank than two weak ones, they sold its assets to the Peoples Bank, where Mr. Farmer was a director.

In reality, the purchase weakened Peoples Bank, and it failed barely two years later, in March 1929.

For Mr. Farmer personally there were ups and down. A daughter, Finonia, died just hours after birth Dec. 11, 1926. Another daughter, Marcella, was born in 1928.

The businessman kept at it. In November 1924, he bought a moving picture show in Stockton. In 1926, he bought the two lots south of Spring Park where the Zollman Garage had been and built his new garage there, keeping business going at least through 1930, when he listed himself on the Census as a car salesman.

Personal troubles returned with the 1929 failure of the People’s Bank.

The state banking commissioner, acting for the now-closed bank, filed suit against Mr. Farmer in May to collect a promissory note. Details were missing from the newspaper story, but the fact a director owed money to the failed institution would have further inflamed hard feelings created by the failure and a general belief that some or all the directors had withdrawn their money before closing the bank.

Mr. Farmer and all the bank’s other directors and officers were charged by Cedar County authorities with multiple counts of continuing to take deposits into the bank after they knew it was failing. President William T. Long and cashier E. F. Peer, both longtime, prominent Jerico residents, were convicted and sentenced to prison in 1930.

Mr. Farmer’s trial in March of 1931, held in Vernon County on a change of venue, featured an “unusual array of legal talent” according to the Nevada Mail story. “The law firm of Neal Newman and Turner of Springfield, George Ramsey and R. K. Phelps were the attorneys for the defendant, and attorney O. O. Brown and Thomas Embree, prosecuting attorney of Cedar County, and the firm of Collins and Osborne represented the state in the trial of the case,” the Mail reported.

The story said the jury was out until 8:30 p.m. before reporting it was hopelessly deadlocked. Mr. Farmer’s “array of legal talent” had succeeded in avoiding a conviction, and the trial foreshadowed both his use of high-powered lawyers when he was in trouble and his frequent requests for a change of venue out of Cedar County, whose authorities, he always argued, were prejudiced against him because he was a Democrat.

Cedar County eventually dropped the charges against Mr. Farmer and the other bank directors after the Missouri Supreme Court, in rulings handed down in 1931, overturned the convictions of the bank’s president and cashier.

TRANSITIONS

Though Mr. Farmer listed himself as a car salesman in the 1930 Census he had at least one other business in Jerico, a general merchandise store. The El Dorado Springs Sun reported in October, 1932 that burglars, hitting the store for the second time in two years, stole its tobacco products, shirts, overalls and various grocery items. Five cases of eggs may have been the most valuable loot, given the ever-harder times settling upon Cedar County.

In late ’32, Mr. Farmer gave up on the business that had brought him to Jerico more than a decade earlier. The “prosperous farmers” who made his auto sales and service garage boom in its first few years no longer existed in sufficient numbers. The few who had money weren’t spending it on cars, and Mr. Farmer pulled the plug.

The Lockwood Luminary reported Oct. 14 that a group of Jerico businessmen had leased Mr. Farmer’s garage for a year and were converting it into a community center. Among other things, it would provide an indoor basketball court for the high school, which didn’t have one. (The building reverted to use of a garage and filling station for a time but was used again as a community center for decades before being condemned and torn down in 2014.)

Out of the garage business, Mr. Farmer’s principal occupation in the early ‘30s seems to have been buying and selling livestock, with the occasional real estate deal thrown in. His name was frequently on the Stockton papers’ weekly lists of Cedar County residents selling stock at Union Stockyards in Springfield.

He engaged in shadier ventures.

In January 1930, he reported his car, which was insured, had been stolen. But when the car and thief were tracked down in Kansas City by authorities, they soon arrested Mr. Farmer, too.

He was charged in Dade County with receiving stolen property. The allegation was he bought a stolen Chrysler from the man who then “stole” Mr. Farmer’s Chevrolet. The case lingered for more than a year before being dismissed in March, 1931.

In 1932, at age 39, Mr. Farmer took his initial step into elective politics, setting a course that would define him for the rest of his life. He jumped into the race for Democratic committeeman for Benton Township, along with C. T. McNeill. and D. C. Baird.

Mr. McNeill, the incumbent, won with 159 votes to Mr. Farmer’s 86 and Mr. Baird’s 18.

Defeat didn’t deter Mr. Farmer. First, though, plans for politics and everything else went on hold Nov. 17, 1933, as word raced through Cedar and Dade counties like wildfire: A first-degree murder warrant was out on Bill Farmer in the previous night’s shotgun slaying of his uncle, C. C. Montgomery, at Mr. Montgomery’s home about 8 miles south of Jerico.

THE MONTGOMERY MURDER

Christopher C. Montgomery, 75 at the time of his death and described in the newspapers as a “prosperous farmer,” was married in 1879 to Eliza Farmer, sister to Bill Farmer’s father. Bill Farmer and his Uncle “Bud” were said to get along well and known to do business deals together.

After Eliza’s death, in September 1931, Mr. Montgomery was “much in the news,” the Greenfield Vedette reported in its story about the murder.

“Apparently developing a taste for liquor and wild parties,” Mr. Montgomery turned his home into “a bachelor’s hall” that “attracted strangers regarded by the community as doubtful characters.” His “new friends” were said to be bilking him of “sums running into hundreds of dollars,” the Vedette reported.

Mr. Montgomery and his hired hand, Ralph Kellar, had been tortured in a robbery attempt a few months earlier. They were doused with kerosene and threatened with fire if they didn’t reveal where Mr. Montgomery’s supposed stash of cash was hidden. The two were saved by the chance appearance of a group of neighbors.

Mr. Montgomery, too, had been a central character in a sensational trial completed just days before his murder. A woman named Lucille Austin, of Lockwood, filed a damage suit seeking $12,000 ($200,000 in 2020 dollars) from some of Mr. Montgomery’s children and their spouses. She alleged the group, finding her at Mr. Montgomery’s home one night, beat her with switches and small tree branches as they drove her away. The Optic said she had been modeling a nightgown for him when his children appeared.

The trial ended in a hung jury.

Mr. Kellar, Mr. Montgomery’s hired hand, told authorities that about 8 p.m. on the night of the murder, Bill Farmer came for whiskey. While they were talking, he said, Mr. Farmer had mentioned there was a man waiting for him in the car. Mr. Keller said he was later sent to the corn crib to put whiskey stored there into a bottle for Mr. Farmer, and while doing so heard two shotgun blasts.

Peeking in the window of the house, he saw a bloody Mr. Montgomery on the floor and fled for help. When he returned, Mr. Montgomery was dead and there was no sign of Mr. Farmer or the purported second man. Murder warrants were issued, one for Bill Farmer and one for a “John Doe.”

The ensuing manhunt, which included a search of the Farmer home in Jerico, came up empty-handed. But on Sunday morning, some two and a half days after the shooting, Mr. Farmer, accompanied by his father, turned himself in to the Dade County sheriff in Greenfield.

He told the sheriff that on the day of the murder, he had gone hunting with a stranger, a Mr. Woods from Kansas City. Later in the day, he said, Mr. Woods suggested they go to Mr. Montgomery’s to get some whiskey.

Mr. Farmer said he left Mr. Woods in the car while he went inside to conduct the whiskey transaction. But, Mr. Farmer said, while he and his uncle talked, Mr. Woods appeared in the door of the house and fired two shotgun rounds into Mr. Montgomery.

Mr. Farmer said that, fearing he would be shot next, he fled the house, but was cornered in the yard by Mr. Woods, who forced him back into the car. He said he was held for two days in the woods at some spot near Wagoner, northeast of Jerico and about 15 miles from the murder scene, before being released with a warning not to report what had happened until Monday, under penalty of being murdered himself. He had then walked to his father’s house south of Jerico, staying out of sight as he did so, he told the sheriff.

People were skeptical.

“The statement…appears very weak and full of flaws and he will no doubt have much explaining to do,” said the Cedar County Republican. The Jerico Optic said that neither the people of Jerico nor Mr. Montgomery’s sons believed Mr. Farmer had killed his uncle, but “they do think he knows who the man was, and they are holding it against Bill until he comes clean and tells who it was.”

Held without bond in the Dade County jail, Mr. Farmer stuck to his story until the day before his April 24, 1934 trial was set to start. His lawyers attempted then to negotiate a deal in which Mr. Farmer would plead guilty to manslaughter in return for a five-year prison term, according to a Vedette story published after the trial.

No deal was reached and the trial proceeded.

As it began, the Vedette described Mr. Farmer as “short, fair and of slight build, which accounts for his nicknames of ‘Little Bill’ and ‘Cotton Bill.’

“Clean-shaven, well dressed and of calm demeanor, he showed little outward evidence of the strain of months of imprisonment under a capital charge, his appearance more like that of a business man engaged in a civil suit than a man on trial for his life,” the paper continued.

The Vedette, like the Nevada Mail had in reporting on Mr. Farmer’s bank trial four years earlier, took note of the “impressive array of legal talent” on hand. The Springfield law firm of Neale, Newman and Turner again represented Mr. Farmer in what the Optic called “the most sensational trial held in Dade County for the last 25 years.” The Dade County prosecutor was aided by an assistant attorney general out of Joplin and by Cedar County’s O. O. Brown, who had helped prosecute the bank case against Mr. Farmer.

The state’s theory was that Mr. Farmer had killed his uncle to prevent him from finding out Mr. Farmer had either forged the signature on a check from Mr. Montgomery or altered the amount on it. Though a teller at Mr. Montgomery’s bank testified she thought the signature not really Mr. Montgomery’s, Mr. Farmer said the check was legitimate, payment in one of the business deals between he and his uncle. He once again told his story about the mysterious Mr. Woods.

Though the Vedette said there was general agreement that Mr. Farmer had done his case great harm with his testimony, jurors saw it otherwise. They took barely two hours to reach a not guilty verdict. The Optic said the first vote was 10-2 for acquittal, the second 11-1, and the third 12-0.

TURNING TO POLITICS

Much changed during the six months Mr. Farmer spent in jail awaiting trial in the Montgomery murder. Prohibition had ended in December, 1933, but whatever societal ills were thereby cured didn’t extend to the economic issues driving the Great Depression, which had but grown worse, with unemployment and farm failures soaring.

In Washington, Franklin Roosevelt and the Democratic Congress swept into power with him in 1932 were busy creating the alphabet soup of agencies intended to ease the plight of millions of impoverished workers and farmers.

In Missouri politics in May, 1934, all eyes were on a three-way race for the Democratic nomination to the U. S. Senate. The candidates were Harry Truman, a Jackson County official backed by Kansas City political boss Tom Pendergast; Jacob Milligan, a congressman backed by U. S. Sen. Bennett Clark; and John J. Cochran, a former congressman backed by the Igoe-Dickmann machine in St. Louis.

Later events strongly suggest Mr. Farmer, who had no official party post, nevertheless worked assiduously on behalf of Mr. Truman, who won the August primary. While Mr. Milligan carried Cedar County handily, Benton Township, where Mr. Farmer would have done most of his work, cast 88 votes for Mr. Truman, just two short of equaling the combined vote for the other candidates. It’s the kind of thing politicians notice.

Mr. Truman went on to win the General Election in November, and the stage was soon set for Mr. Farmer’s formal entry into politics and an accumulation of power and influence.

In early 1935, federal relief administrator Harry Hopkins, acting on the recommendations of Senators Truman and Clark, named Kansas City public works director Matthew Murray as head of the newly formed Works Progress Administration’s operations in Missouri. Mr. Murray was Mr. Pendergast’s creature and his appointment amounted to turning control of WPA’s Missouri operation over to the boss.

“(Murray) bent over backwards to reward Pendergast partisans,” wrote the Missouri historian Richard Kirkendall.

There were to be tens of thousands of jobs to reward In Missouri as the WPA swung into action. A good many would be in impoverished Cedar County, where Bill Farmer now stood well with the Pendergast faction.

So it was that in September 1935, when the WPA announced a project to regrade and re-gravel 32 blocks of streets in Jerico, Mr. Farmer was named foreman on the $2,187 job ($42,000 in 2020 dollars). The Optic story said as many as 30 men would be hired at 20 cents per hour – $32 per month, decent pay at the time and place. Bill Farmer would pick the men, with the only restriction being that they be on welfare. There were plenty of those, of whatever political stripe preferred.

Two months later, Mr. Farmer additionally was named sub-foreman in charge of the western half of a WPA project building a gravel road running from the Vernon-Cedar county line east through Osiris and Wagoner to Missouri Route 39.

The year ended with Mr. Farmer adding a business to his holdings. The Optic announced on Dec. 27, 1935 he had purchased Spikes Drug Stores on Main Street in Jerico from Dr. H. M. Spikes.

THE POLITICIAN

1936 was a watershed year for Mr. Farmer and for Tom Pendergast, whose machine gave him his start.

At age 44, Mr. Farmer won his first party office. He faced his first charges of violating election laws. He won praise for his work on the WPA road projects and awarded a bigger role.

The July 3, 1936 Optic said, “J. W. Farmer, local foreman, and H. H. Swisher, local timekeeper, have did (sic) a nice piece of work, both on the road project south of town and the street project in town.” The men and their crew moved on to the Vernon County-Route 39 project north of town, the paper said.

Mr. Farmer found time for politicking, of course. When the Aug. 6 Primary Election rolled around, he easily won the Benton Township committeeman slot, getting 251 votes to 113 for J. A. Reynolds.

Within weeks, though, Cedar County Prosecuting Attorney Lewis Hoff filed bribery charges against Mr. Farmer and a second newly elected committeeman, alleging they had traded jobs on WPA projects for votes in the committeemen’s races. The two counter-attacked, accusing the prosecutor of soliciting a bribe, saying Mr. Hoff had offered to forego the charges in return for a cash payment. The Democrats also produced an affidavit from an ex-convict saying he had once paid Mr. Hoff $50 to get a charge dismissed.

A special two-judge panel decided the accusations against the prosecutor were baseless. Mr. Farmer won a directed verdict of acquittal at his trial in March 1937 when Mr. Hoff’s witnesses did not appear.

The affair did nothing to hinder Mr. Farmer’s rise. In mid-November, 1936, with the charges against him pending, the WPA promoted him from sub-foreman to foreman on the Vernon County-to-Route 39 project, giving him additional hiring power.

The township committeeman job introduced Mr. Farmer to a new level of politics, giving him an official voice as the county’s Democratic central committee discussed candidates, decided policy and raised money.

He won re-election as committeeman in 1938 by 263-27, over a write-in candidate, but his rise soon encountered trouble rooted in an all-out federal assault on Tom Pendergast that began General Election Day, 1936.

As the vote count ended, armies of federal agents armed with grand jury subpoenas seized ballot boxes throughout Kansas City. Examinations showed many thousands of ballots had been altered; hundreds of people were indicted over the next 18 months and 271 were convicted or pleaded guilty on vote fraud charges. Mr. Pendergast escaped without charges personally but his machine was crippled even before he later went to prison for income tax evasion.

Everyone connected to Mr. Pendergast was soon under attack, including Matthew Murray and his conduct of the WPA’s Missouri operations, in particular the widespread reports of hiring abuses. He was forced out and in October, 1939, was indicted on income tax evasion charges.

One change his critics won early in the year was a rule that WPA workers holding committeeman posts had to give up one or the other.

Down in Cedar County, Bill Farmer chose to hang onto the paying job with the WPA, resigning as Benton Township committeeman in summer, 1939.

His decision may have been influenced by the April fire that destroyed his drugstore. He and Mabel were living in quarters behind the business, so they lost their home as well. (The fire, of unknown origin, apparently started in the second floor of Paul Long’s neighboring hardware store, according to the Stockton Journal. Mr. Farmer was insured, the paper said.)

1940: FIGHTING FOR SURVIVAL

The 1940 Democratic primary turned into a fight for survival for Pendergast-linked politicians all through Missouri, from U. S. Sen. Harry Truman all the way down through Bill Farmer in Jerico Springs.

The year started badly for Mr. Farmer, who was fired from his WPA job in February even though he had given up his committeeman’s seat for it. In May a federal grand jury in Kansas City indicted his daughter, Catherine Fontella Kifer, for stealing money from the mail at the Jerico post office. She was assistant postmaster there, and her husband, Olma Kifer, was postmaster. (She eventually entered a plea of nolo contendre and was sentenced to two years probation.)

Mr. Farmer fought back. He filed for Benton Township committeeman against H. H. Swisher, who had been appointed to the post by Gov. Lloyd Stark when Mr. Farmer resigned the previous year in the futile attempt to keep his WPA job.

As the campaign unfolded Mr. Farmer threw grit in the gears, apparently for the sake of grit in the gears. He submitted a list of precinct election judges to the county, though that was the perquisite of the committeeman, now Mr. Swisher.

Mr. Farmer argued that the central committee had never formally accepted his resignation, which meant there was no vacancy for Mr. Swisher to fill and that he (Mr. Farmer) was still the properly elected committeeman. A circuit judge disagreed, accepting instead the list submitted by Mr. Swisher, who quipped “Gov. Stark appointed me and Bill tried to dis-appoint me.”

Statewide, the incumbency offered Sen. Truman no protection from Democratic primary challengers, most prominently from the popular governor, Lloyd Stark. Maurice Milligan, the U. S. attorney for Kansas City who had organized the assault on election fraud, also challenged Sen. Truman. Both trumpeted their roles in bringing down Mr. Pendergast and emphasized Sen. Truman’s links to him.

Sen. Truman, though weakened by his association with Boss Pendergast, narrowly won re-nomination. In Cedar County, the senator got 626 votes to 458 for Gov. Stark and 165 for Mr. Milligan. One-fifth of Mr. Truman’s votes – 125 – were cast in Benton Township, according to results carried in the Cedar County Republican.

Mr. Farmer won back the committeeman job from Mr. Swisher as well, though the Republican didn’t carry the exact vote. The win had to be particularly satisfying, given the rivalries in Jerico at the moment.

Some insight into those is offered in an April, 1940, letter from George Morris, an anti-Farmer Democrat, to Gov. Stark.

The letter appealed for the governor’s support for quick completion of an improved Jerico to El Dorado road. Mr. Morris reminded the governor that he (Mr. Morris) had circulated a petition in 1939 “signed by our best class of democrats” urging him appoint Mr. Swisher to the committeeman job vacated by Mr. Farmer, who Mr. Morris dismissed as “a Pendergast man.”

Mr. Morris further reminded the governor that appointing Mr. Swisher “is why you received all the delegates from here” at a St. Louis convention. Mr. Morris concluded by assuring the governor, “I am doing all in my power to put you over (in the Senate primary).”

When the dust cleared, though, it was Sen. Truman and Committeeman Farmer left standing. I don’t know whether Gov. Stark helped with the road to El Dorado during his remaining months in office.

ON THE RISE

Mr. Farmer’s win in 1940 can only have been a confidence booster and would have enhanced his standing among politicians. He won re-election as Benton committeeman in 1942 and again in 1944, after which he stood for county chairman when the Democrats reorganized after the August primary. He won, and would hold the post for 12 of the next 14 years.

The county chairman’s job pushed Mr. Farmer into the next level of party decision-makers. In addition to directing Democrat affairs in Cedar County, he would join other county chairmen in the 6th Congressional District on the Congressional District committee, giving him a formal role in discussing candidates for Congress, setting policy and raising money on a multi-county scale.

His broadening perspective is illustrated by his attendance at an August, 1946, meeting in Butler at which more than 100 civic leaders from towns around the 6th Congressional District formed the Osage Basin Development Association, the mission of which was to advocate the construction of a dam on the Osage River at Kaysinger Bluff. Mr. Farmer was named a director, which would have given him entrée into the circles of developers, promoters and state and federal officials also pushing the project.

The dam, eventually named after Harry Truman, was authorized by Congress in 1954, with construction beginning in 1964. Combined with related Osage basin dams from the same era on the Sac River at Stockton and the Pomme de Terre near Hermitage, it was the largest public works project ever undertaken in southwest Missouri.

In 1948, other members of the congressional committee picked him as their chairman, a post he held until 1952. Now perched in the second-tier leadership of the state party, if not the first, he had reached the zenith of his power and influence. He publicly rubbed shoulders with now-President Harry Truman, as when he and the 12 other Congressional District chairmen served as the official welcoming committee on one of the President’s visits to Missouri.

His ease in the circles of power is illustrated by an anecdote from Dr. Bill Neale of Eldorado, from the early 1950s, when Democrat Phil M. Donnelly was governor.

“My dad had employed a fellow to work in the funeral home. He sent him to embalming school, but he could not pass the state test for a license. Dad asked Bill for help, and they drove to Jeff City. They walked into the governor’s office and the secretary said ‘Hello, Mr. Farmer, what can we do for you today?’ Bill didn’t answer but walked into the governor’s office and threw his dirty felt hat on the desk and stated their business. The license was issued the next day.”

Several factors figured in Mr. Farmer’s rise, including the simple willingness to do the grunt work required to turn out voters. As long as he was committeeman, for one small example, he would haul Benton Township Democrats needing a ride to the polls on election day.

Ability to do favors was another factor, from handing out WPA jobs on up. The several anecdotes I’ve heard from Jerico-area people feature the helping-hand stuff illustrated by Dr. Neale’s story. He likely did larger and more consequential favors for the better connected.

The overwhelming factor in his rise, though, would have been money – money for the party, money for candidates, money for whatever needed to keep the wheels turning. With no campaign finance reporting laws to bother with, there’s little record of amounts and exact sources, but it’s easy to guess where Mr. Farmer turned as he built a fund-raising operation.

Besides people willing for philosophical and friendship reasons to write a check to the party or a particular candidate, those getting tapped would have included WPA workers, contractors and suppliers, along with anyone – postmasters, etc. – whose jobs depended on federal appointments now controlled by Democrats.

He regularly led delegations of Cedar County Democrats, often 30 or more people, to party conventions and fundraisers like Jackson Day dinners in Springfield and Kansas City.

Then there would have been the favor-seekers whose wallets are always open to the political in-crowd.

There may, too, have been less licit sources: Mr. Pendergast and his allies, before and after his personal fall, didn’t worry much about the legality of their enterprises.

We do have a couple of peeks into the operation, though one is from 1959, a year after Mr. Farmer lost his party posts. The Kansas City Times reported in September a man walking in downtown Kansas City found a checkbook belonging to Mr. Farmer and, scattered nearby, nine $100 checks made out to the Symington for Senate committee. One was from Mr. Farmer, the others from other people. The Times said the money apparently was for seats at a fund-raising luncheon for Stuart Symington, then one of Missouri’s U. S. senators.

That $900 is equal to more than $7,900 now, a big number for a single fundraising dinner in whatever year. That amount, I’m guessing, is small compared to the money flowing to and from Mr. Farmer at the height of his power in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s.

The second peek into his operation comes from 1955, when the federal government indicted him for lying to a civil service investigator in 1951. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch said the investigator was looking into payments made to the Democratic Party by people hoping for the postmaster jobs in Golden City and Liberal, and for a rural carrier’s job in Liberal.

A federal judge in Springfield eventually dismissed the charge.

Bad men and bad ballots: The 1954 election

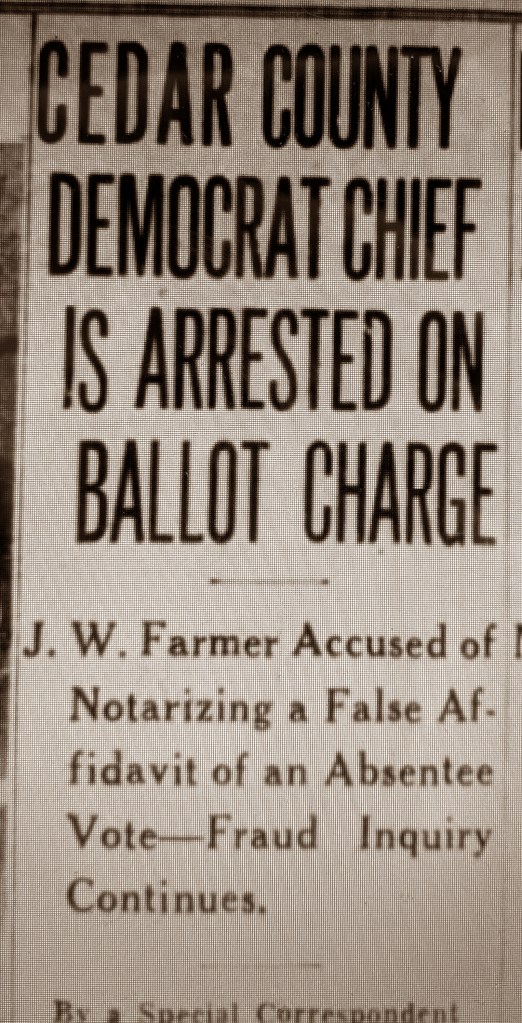

As the 1954 General Election approached, stories about irregularities in absentee voting began making the rounds in Benton Township, Mr. Farmer’s home base. After Election Day, the grumblings grew into an uproar that led to front page headlines all over Missouri, a dozen felony charges against Mr. Farmer and an anti-Farmer revolt in Cedar County.

The scheme, as laid out in court proceedings that stretched into 1957, began several weeks before Election Day, when Mr. Farmer went to John Boone, the Cedar County clerk, and presented an affidavit declaring that 81 Benton Township residents had requested that he bring them absentee ballots.

Though the law required absentee ballots be picked up in person or mailed to the voter, Mr. Boone, after consulting with with Prosecutor Joe Collins, gave Mr. Farmer the ballots.

The two, both Republicans, decided the election laws were “liberal enough to warrant the procedure adopted in Farmer’s case,” Mr. Collins later told The St Louis Post-Dispatch.

According to testimony in subsequent trials, Mr. Farmer did not take most of the ballots to the voters; instead he filled them out however he wished, attached falsified affidavits stating the voter had filled them out in his presence, put them all in envelopes and returned them to the clerk’s office.

Mr. Farmer personally notarized 55 of the ballots and Josephine Thompson, a notary in Jackson County (Kansas City) notarized 17 – those of Cedar County residents who allegedly were in Kansas City and would be unable to vote Election Day.

Since the names of absentee voters are public, questions were soon circulating. After Election Day, when all Benton Township election judges would have seen the list of absentee voters, the questions turned very specific and very loud.

More than 200 Benton residents signed petitions demanding a grand jury investigation and hired long-time Farmer nemesis Lewis B. Hoff to represent them at a court hearing on their complaints. When the sheriff and prosecutor joined the call for an investigation, Judge O. O. Brown (who as prosecutor charged Mr. Farmer in the 1929 bank case) ordered a grand jury impaneled.

As evening closed in the next day, Friday, Feb. 5, 1955, three armed men went to county clerk John Boone’s home south of Stockton. One stayed with his wife and son while the two others took him to the courthouse and forced him to open the safe containing the contested ballots and affidavits. Those were taken, and Mr. Boone, unharmed, was dropped off down the road from his home, at which the telephone lines had been cut.

He told investigators the men knew the layout of the courthouse and his office, and that they were unhurried in making sure they had what they came for.

In the ensuing uproar, the Missouri attorney general dispatched an assistant to join the investigation led by Cedar County Prosecutor Collins. The state police and even the FBI sent investigators, the Republican reported.

The paper got to the key point: “It is assumed that without the ballots it will be much harder to ‘make a case’ against anyone who might be charged with violation of the law in connection with them.” So it turned out to be.

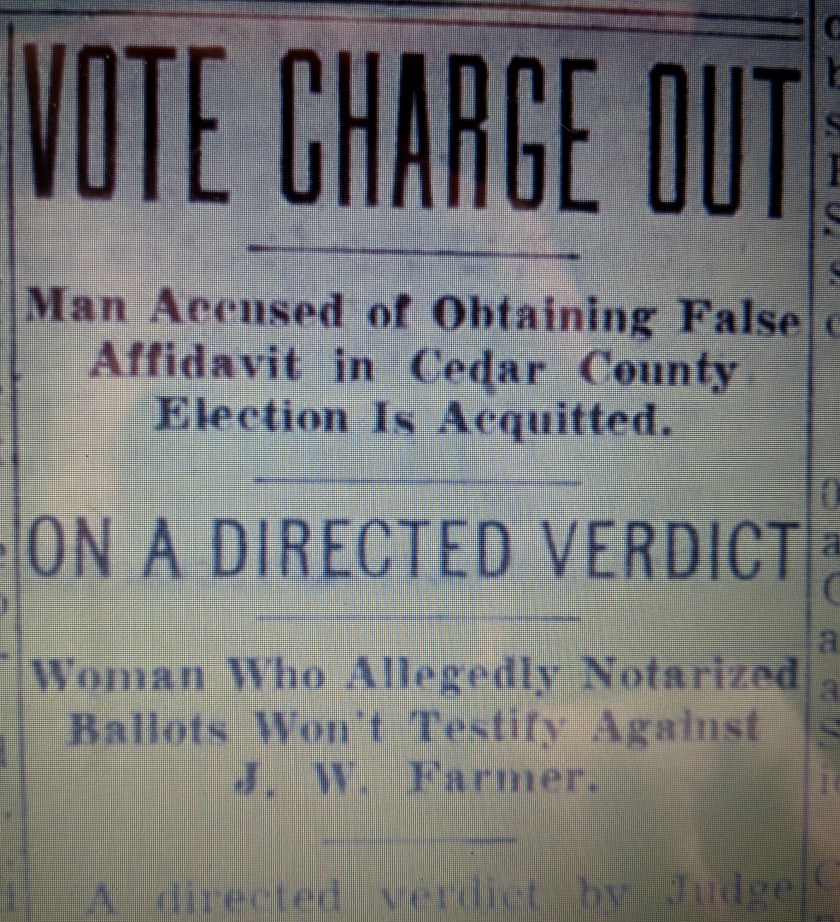

Officials tried, with the Cedar County grand jury eventually lodging five charges accusing Mr. Farmer of “feloniously affixing his notarial seal to a false affidavit of an absentee ballot.” Eight counts of “obtaining false affidavits” were filed by the grand jury in Jackson County, where some of the alleged absentee voters had supposedly marked their ballots.

Mr. Farmer requested a change of venue in the Cedar County cases and two were transferred to Lawrence County (Mount Vernon) and three to Jasper County (Carthage). He was eventually exonerated in all five. “Making a case” was indeed hard without the ballots and affidavits.

The state took its best shot in the Jackson County cases, in which the charge was ”obtaining false affidavits” and their witness list included Josephine Thompson, the Jackson deputy sheriff/notary who had notarized some of the ballots when asked to do so as “a favor to the boys down in Jerico.”

The Kansas City trial

As the trial got under way in Kansas City April 24, 1956, a Springfield News-Leader story somewhat eerily echoed those in the Nevada Mail when Mr. Farmer’s bank trial began 26 years earlier, and in the Greenfield Vedette at the beginning of the Montgomery murder trial 22 years before.

“A brilliant array of Ozarks legal talent will be on display in Kansas City today for the trial of J. W. Farmer, Democratic political leader of Jerico Springs,” the paper said

Mr. Farmer’s attorneys were Sam W. Wear of Springfield, a former U. S attorney for the Western District of Missouri, and Jean Paul Bradshaw, also of Springfield, who had been the Republican candidate for governor in 1944. Assistant Attorney General Don Kennedy of Nevada led the prosecution, backed by two Jackson County deputy prosecutors.

In a trial that played out in the glare of a statewide spotlight provided by the St. Louis and Kansas City papers, and working without the stolen ballots and affidavits, Mr. Kennedy called election judges (including my cousin, Virgil Beydler) who testified as to the names of absentee voters they remembered seeing.

Several of the alleged voters (including my uncle Lester Beydler and first cousin Sam Forest) testified they had not asked Mr. Farmer to get them a ballot and had not voted absentee in the election.

But Prosecutor Kennedy hit a stone wall when he called his 10th and final witness, Josephine Thompson, the deputy who had told the Jackson County grand jury she had notarized 17 absentee ballots at Mr. Farmer’s request even though she never saw the people.

Viewed as the state’s star witness, Mrs. Thompson, when called to the stand, refused to testify beyond stating her name. Pleading her Fifth Amendment protections against self-incrimination, she refused to answer all other questions.

The prosecution, trying to save its case, attempted to call Jackson County deputy sheriff Roy Hayes, who had introduced Mr. Farmer to Mrs. Thompson, but the judge refused to permit it on the grounds the deputy had not been on the advance list of witnesses. He then granted a defense motion for a directed verdict of not guilty, the Kansas City Times reported.

Jackson County authorities tried again. In September, 1956, both Mr. Farmer and Mrs. Thompson were indicted but on May 2, 1957, a judge granted a defense motion to dismiss the charges on the grounds the indictments failed to state sufficient evidence, according to the Times.

Once again, Mr. Farmer had skated, this time thanks to men willing to execute the brazen theft of the ballots, and to a Jackson County deputy’s refusal to testify.

Court outcomes aside, the episode eventually ended Mr. Farmer’s public political career. He had won re-election as both Benton committeeman and county chairman in 1956 despite the uproar and aborning opposition in Cedar County.

By 1958, though, Cedar County Democrats were done with him. He did not seek re-election as Benton Township committeeman, thus rendering himself ineligible for another term as county chairman. He could not have won anyway. The Kansas City Times, in a long analysis, said 11 of the 14 Cedar County committeemen elected at the August primary were anti-Farmer.

In the end, the entire ballot mess apparently was pointless. Though the 1954 election in Cedar County saw a Democrat win a county-wide office for the first time in 26 years, his margin of victory was easily wide enough that the absentee ballots made no difference.

END GAME

Sixty-six years old when he lost his party posts, Mr. Farmer would live another 25 years, all but the final year or so where he’d always been – around Jerico and Lockwood.

Mabel had died in 1953, and his son, Wayne, in 1957, when he was but 41. Both daughters had moved to Oklahoma.

Mr. Farmer did not like living alone, said Mrs. Martin, the great niece. After Mabel’s death, he’d moved in with his sister, Nora Evans, and her husband, Ralph, who lived in Jerico, where Ralph managed Mr. Farmer’s drugstore/pool hall.

Though lacking official standing in the party, Mr. Farmer continued at least for a while to raise money for Democrats, as witnessed by the 1959 lost-checkbook incident.

He could still do a favor. Carolyn Grisham, (nee Farmer, a distant cousin) tells the story of a young relative who, graduating college with an accounting degree in the early ‘60s, wanted a job with the state. “Uncle Bill” took him to Jefferson City, to the Capitol, and introduced him to a man in an office there. The job was had.

There are contrasting portraits of Mr. Farmer in this period, each drawn by young-at-the-time relatives whose lives intersected closely with his as he reached his mid-60s.

One is from Linda Martin, the great niece who got an intimate look into Mr. Farmer’s life as the ‘60s began. Then about 10 years old, she moved in with her grandparents, the Evans’, where he was living. The household moved to Lockwood about 1961, after Mr. Farmer’s store burned.

Mrs. Martin said he began each day with a beer and a shot of whiskey. It’s what kept him young, he told the pre-teen girl. Turning the radio on, cranking up the music and dancing by himself was often a part of his morning routine, she said.

There was a darker side to life with ‘Will’, as her grandparents called him. There were the guns and the fear.

He never left the house with fewer than two guns. At night, he insisted the blinds be drawn. At bedtime, the doors had to be locked. He startled markedly at unexpected noises. At bedtime, he would leave a long gun leaning against the wall on each side of the front door and take two pistols to bed with him.

The resulting atmosphere produced this incident from her girlhood, Mrs. Martin recounted.

As Linda prepared to go downtown for a movie, her Grandma Nora reminded Will not to lock the child out if he went to bed before she got home. Nevertheless, Linda found the door locked when she arrived home after the movie. Fearful of her great-uncle’s reaction if she knocked, she spent the night on the porch.

When Nora got up the next morning and found Linda outside, she gave her brother a tongue-lashing. As he sheepishly apologized, she sharply interrupted him: “Will, if you weren’t so damn mean, you wouldn’t need so many guns.”

Mrs. Martin said she heard later that a commodities futures deal gone wrong was the source of the fear.

More pleasant scenes fill the memories of Randy Farmer and his sister, Elaine McClary, the children of Mr. Farmer’s son, Wayne, who lived in Neosho when he died at age 41 in 1957. Elaine was 10 and Randy 7.

“He was a big help to me and my brother,” Elaine said in a 2020 conversation.

“Granddad stepped in and spent a lot of time with us when Dad died,” Randy recalled.

Elaine said Mr. Farmer promised his dying son he would come every week and take her to her piano lesson. He did so, each Tuesday driving the 6o miles from Jerico to Neosho, where his grandchildren lived. Picking up Elaine, he would take her an additional 70 miles to her lessons in Pittsburg, Kan. Elaine remembers the drives as times when she talked with her grandfather about whatever was going on in her life and “just everything.”

They always stopped at the same store each trip for a soda and potato chips, a store among those her father had audited in his job with the Missouri Department of Revenue, she said.

Back in Neosho, Mr. Farmer would spend time with Randy, including attending his baseball games and other childhood events. “I loved Granddad,” Randy said. “He was great.”

The two saw him his less frequently as they went off the college, but maintained contact. He helped with college costs and arranged for grad school loans, said Randy, who ended up with a Ph. D. in higher education. Elaine holds a master’s in music and plays the violin and oboe as well as the piano.

Randy, like others, recalls his Granddad as a snappy dresser, sometimes wearing three-piece suits with his usual straw hat and “looking very dapper.”

Randy said his grandfather would sometimes tell stories of having known Harry Truman and Tom Pendergast. “We thought, sure, but wondered, you know, how much of it was true.” But when talking with lawyers in Cedar County while tending to estate-related matters, he discovered, he said, that, yes, the stories were true. (Both Randy and Elaine said after reading an early draft of this profile they had learned a great deal they had not known about their grandfather.)

Sometime around 1963, with brother-in-law Ralph in a nursing home and sister Nora’s health failing, Mr. Farmer was forced to find a new home. He had a house in Lockwood for a time. During the mid-and late- ‘70s, he lived south of Jerico, just off Route 97 on the Greenfield Cemetery road.

He continued to buy and sell land. Cattle, too, I’d guess, though I’ve got nothing concrete to demonstrate it.

Both Mrs. Martin and Charley Farmer told the story of a night during his Lockwood residency when he somehow drove his car into a train. (He was a notoriously bad driver.) Unhurt, he climbed from the wreckage and stalked down the street toward his house, a pistol dangling in each hand, cursing at the top of his voice. Charley Farmer said Bill sued the railroad and won a judgement.

Charley, who still farmed near Lockwood in 2020, was understated when summing up his cousin: “I guess you could say he was the black sheep of the family.”

Mindi Culbertson, of El Dorado, said her family moved south of Jerico in 1975 or’76, during the time Mr. Farmer lived there. She said her father, Louis Stuedle, often served as Mr. Farmer’s driver over the next several years.

“(Bill) always had a new car. Dad would drive it anywhere Bill wanted to go. There were times I recall Dad leaving with him and be gone several days but would never really talk about where they went or what they did.”

Sometime after 1980, near or at 90 years old with his health worsening because of Parkinson’s, Mr. Farmer moved to Oklahoma, where his daughters lived. Granddaughter Elaine said he also became a Christian around this time, accepting Jesus and being baptized.

He died at Pryor, Okla. in 1986 at age 93. He is buried in the IOOF cemetery in Neosho, near his son, Wayne.

He leaves a final mystery there. Though Mabel, his wife, was buried in Dade County when she died in 1953, Mr. Farmer has a double tombstone. The second name is that of their first daughter, Fontella Kifer, with the death date blank. She died 17 years later, in 2003, and is buried in Las Vegas, Nev.